Released in 1941, Citizen Kane is considered one of the greatest movies of all time. The story follows a reporter investigating the last words of the famous Charles Foster Kane. Told through flashbacks and interviews, the dynamic storytelling and cohesive themes distinguish the film from other such pieces of its time. But does it hold up to modern audiences? Is there anything that we can learn from Citizen Kane, or is the story a thing of the past? And do more recent films taking inspiration from the iconic movie live up to the iconic legacy?

When I settled into watching the esteemed film, there was little that I could do to go into the experience oblivious to certain aspects (something about a sled) in the same way that one cannot watch the Sixth Sense for the first time without having some degree of awareness about the twist (think: “I see dead people”). What followed was two hours of a brilliantly written mystery, masterfully executed, and unlike anything I’d seen before.

In Citizen Kane, Charles Foster Kane, the owner, and publisher of The New York Daily Inquirer dies. His last word “Rosebud,” becomes the center of an investigation conducted by reporter Jerry Thompson. Thompson speaks with an array of unreliable narrators connected to Kane in some way or another. And gradually, through the testimony provided, the portrait of a broken man begins to develop.

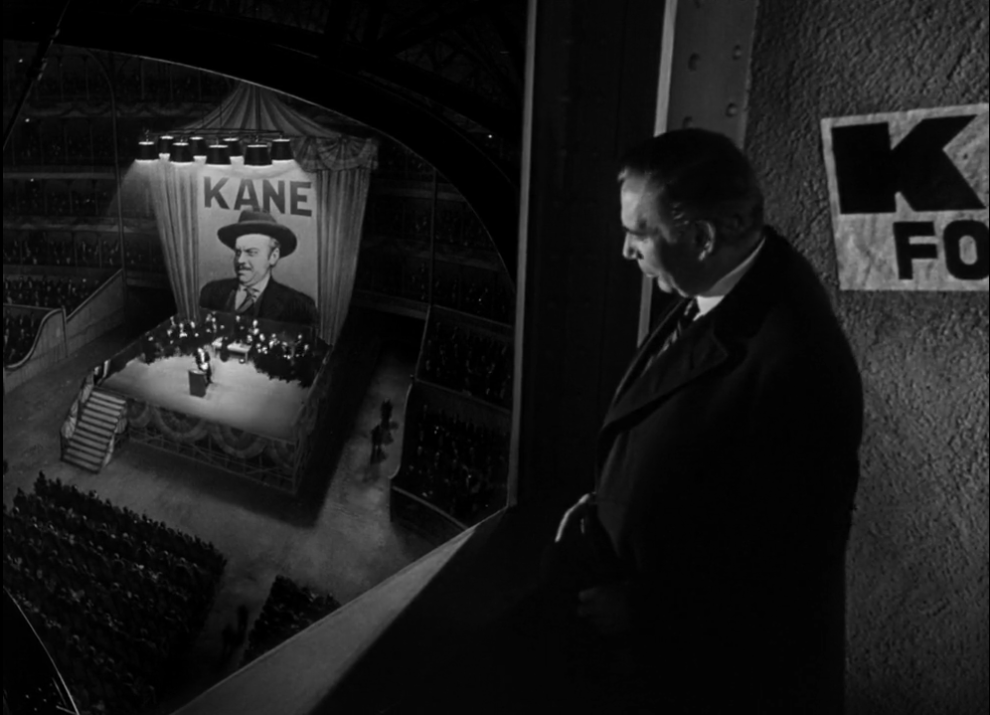

The only thing the interviewees seem to be able to agree on was that Kane engrossed himself with earning the love of others, going so far as to run for public office while having an affair: never satisfied with what he already had. He also appears to be incapable of loving others, a stark commentary on the nature of individuals illuminated by the limelight. So, although the film is distinctly mid-20th century, the themes at its core are very much timeless, perhaps even more so considering the state of pop-culture today.

During his campaign for public office, Kane promises to end the tirade of prominent political machine Jim W. Gettys, a character largely inspired by Charles F. Murphy of Tammany Hall. When Gettys leaks the story of Kane’s affair to the press and his wife, Kane’s entire political career is ruined. Even though this part of the film is written for the screen in that it is purposefully dramatic and sordid, it paints a powerful picture demonstrating how corruption can obstruct true justice.

Interestingly, Citizen Kane is reported to be a favorite film of former President Donald Trump. His biographer, Tim O’Brien, has even said that Trump identifies with the character of Charles Foster Kane. America’s history is plagued with corruption, a theme that films like All the President’s Men work to portray. There is yet to be a point in time where such an idea is peripheral, and until such an age comes to be, this message will remain thoroughly apropos.

Cinematically, the movie is a triumph. Hordes of essays have been written about the magic of the reflections, camera angles, composition, transitions, and overall flow of the entire piece. Even without the brilliant writing, the movie stands as a tribute to the art of cinematography and the magic of Hollywood.

Mank, directed by David Fincher, came out on Netflix in November of 2020. Starring the iconic Gary Oldman in the eponymous role, the film follows a portion of the life of Herman J. Mankiewicz, who was the primary creator of the Citizen Kane screenplay. It intends to illustrate the inspirations for Citizen Kane through the presentation of interactions between Mankiewicz and suspected inspirations for characters, such as William Randolph Hearst for the role of Kane or Marian Davies for Kane’s mistress. It also heavily dabbles in a subplot about Mankiewicz’s involvement in the California gubernatorial election of 1934. The film itself is not entirely historically accurate, and though it is well-acted, there are few other redeeming assets.

Mankiewicz’s character feels cookie-cutter and repetitive of tropes seen countless times before. He is portrayed as an intelligent, caring man whose only vices are alcohol and gambling. Well-written characters have believable flaws, but Mank’s feel lazy as if the writers were unable to overcome their pride when writing him.

The film is intended to be strongly reminiscent of Citizen Kane, hence the black and white coloring and stylistic choices aligning the films together. But not only does Citizen Kane serve as a strong inspiration for Mank, but it also informs nearly every moment. Logically, it makes sense that Fincher would want Mank to emulate Kane, to draw parallels between the two and create a more compelling story. But Mank doesn’t elaborate on the template, it merely exists within it.

Nearly eighty years have passed since the release of Kane, a period in which filmmaking has flourished, and yet no new methodology has been applied. It comes off as a poor emulation of the very film it claims to cite as its catalyst of creation. While Citizen Kane uses non-linear storytelling to create a dynamic plotline, the flashbacks spliced throughout Mank feel forced and occasionally hard to follow. Constantly flipping between subject matters, there are far too many elements intertwined for a clear message to shine through.

The story of Mank tries to be too many things. In one regard, it explores the political climate of the time. By exploring the corruption of the 1934 California election for governor, it connects real-life events to the politics featured in Citizen Kane. But the fervent support for candidate Upton Sinclair that Mank is saddled with doesn’t accurately represent the more conservative views held by the real Mankiewicz.

Another aspect that feels out of place is the creation of a character named Shelly Metcalf. In the film, Metcalf helps to create a series of staged “man-on-the-street” videos portraying supporters of Upton Sinclair as white foreigners or people of color. Sinclair’s conservative opponent, Frank Merriam, is painted in a positive light by being supported by American white people. When Merriam wins the election, overcome by guilt, Metcalf commits suicide following a strange interaction with Mankiewicz in which he admits to having Parkinson’s.

In reality, there was no Shelly Metcalf, although the staged videos were very much real. The event is supposed to act as a motivator for Mank to write a screenplay divulging corruption in politics and painting individuals like Hearst (who Kane is supposedly based on) in a negative light. However, the entire affair feels out of place, as if Mankiewicz was unable to find the inspiration to write Citizen Kane of his own volition.

In both films, diversity is virtually non-existent. Citizen Kane was created in a time when individuals who weren’t white and weren’t men simply weren’t cast in meaningful roles, and though the time period doesn’t excuse this phenomenon, it certainly explains it. On the other hand, Mank fails spectacularly at featuring interesting, female characters. Sara Mankiewicz, the wife of Herman Mankiewicz and portrayed by Tuppence Middleton, merely exists as a companion to her husband and serves virtually no purpose.

The only other remotely significant female character is Marion Davies, as played by Amanda Seyfried of Jennifer’s Body fame. Though not blatantly offensive (a wonderfully low bar), Davies comes off as oblivious and occasionally self-absorbed. At one point, she declines to confer with an industry executive on behalf of Mankiewicz because she “already made her exit [from the media company],” refusing to surrender any drama created by her departure. While Kane’s lack of diversity can be attributed to the era in which it was created, Mank’s inclusion of female characters is a sorry excuse for equality.

Citizen Kane is regarded as one of the greatest movies of all time, a sentiment that I understand and share. That being said, the movie should exist solely within its place in film history, as there is extensive room for improvement in every corner of the film industry. By modern standards, the film can appear occasionally outdated, a feature unintentionally emphasized by films such as Mank which seek to imitate the genius of the film. However, the biggest lesson that such models can teach us is that great films should be confined to their own time periods. Strokes of genius like Citizen Kane are one of a kind. Perhaps instead of recreating stories already told, Hollywood should focus instead on lifting the voices they prosper in silencing.