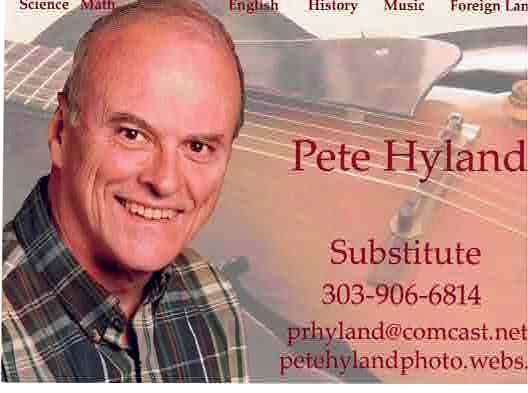

Substitute teacher Pete Hyland sweeps into a classroom like a time traveler. He sets up on the teachers desk with a brown leather briefcase. While he’s watching over the class Mr. Hyland rarely smiles, but looks content and confident, like a Nascar driver with a Lamborghini on cruise control.

“I started teaching right out of college in New York City… in 62,” Mr. Hyland told me, an accent beginning to slip into his voice, “I was there for 9 years.”

From 1962-1967 Hyland worked as a math and science teacher at Port Richmond High School on Staten Island, where he grew up. As he graduated from college the Vietnam war was ramping up. As he was hired for the job he was told to inform the draft board yearly of his new profession.

“I said, ‘why?’ I was so naive…I didn’t know that teaching was, what they called, a ‘critical occupation,’ so if you’re a teacher, they won’t draft you,”

He mused about a letter he got from the draft board, “Greetings, from your Uncle Sam,” was the customary greeting. He talked about how close he came to going to the army, and about what it was like for his students who were drafted.

“Thomas Pidaro, he came back from boot camp and I said, ‘oh Thomas look at that shiny uniform,’…then a year later there was a board inside the entryway of the school, ‘Killed in Vietnam,’ in big gold letters, and the first name up there, Thomas Pidaro… anyway that was the 60s, and that’s what it was mainly about,” said Mr. Hyland.

Mr. Hyland reflected more on the defining moments of the last 70 years, “There was Kennedy’s assasination in ‘63, and then later there was RFK’s [Robert Kennedy] assasination…” he trailed off then:

“Anyway, got married, and didn’t want to raise a family [in New York]… you ever been to Staten Island?” he asked.

He drew me a “real quick picture” of the boroughs of New York. He gave me a tour of the counties, “well everyone knows this is Brooklyn, but officially it’s Kings,” he spoke out as he scribbled the water in the bay. Then he drew the blob of his home, Staten Island, and told me that it used to be rural, but it was changing with the rest of 70’s New York, an early gentrification as the city moved to the country and the country moved to the suburbs of New Jersey.

“We said [him and his wife], let’s come out here [Colorado], and it was the best move we ever made,” said Hyland.

Although it may seem like Colorado was a jump from New York City, Mr. Hyland says that teens are pretty much teens wherever, whenever. He humored me about long hair, subcultures, and hippies at the highschools he taught.

“Kids would come home from Vietnam, and they were lucky to come home, and they would be taunted by people who opposed the war,” said Hyland.

But there was a flip side to the teenagers and protestors advocating for peace. Hyland mentioned the extreme brutality towards students during sit ins and protests. Then the conversation swung back.

“Heritage was just opening… and that was ‘72… and I was there 16 years then they moved me over here [Littleton] because they needed a chemistry teacher,” said Mr. Hyland.

Mr. Hyland worked at Littleton for nine years, from 1988 to 1997, he knows the school as well as anyone teaching, he watched the administration gut the science wing and ask for a wishlist from the teachers.

“We got everything we asked for, we were the envy of the whole school,” said Mr. Hyland.

Of course that means the lab tables were put in in ‘88 and are beginning to show their age, but he reflected on that change fondly anyway. He’s now in his 23rd year of subbing, and, although he said most other teachers leave with a sour aftertaste, he still enjoys teaching.

He reflected on the way that science textbooks were first re-written, as the US tried to make a push for science, after Russia launched Sputnik. How he sees the same reasoning in the expansion of STEM as a push back against relentless innovation overseas in China. Also, the generational pressure put upon him as a kid, the limps on his teachers and elders when they came back from World War 2. How “ok, boomer” seemed like the same inter-generational angst that’s always been around. The one concession he made of how teens have changed was with technology.

“This has changed kids,” Hyland said gesturing towards a Chromebook.

Nostalgically he talked about the first computers he saw at schools, then the one room computer labs, then the classroom personal computers, and now finally Chromebooks. He called the current case of distraction with technology a “constant battle”.

“I really don’t know if I could take it,” Mr. Hyland said.

Mr. Hyland may well be a master teacher. In one form or another, he’s been teaching for over 50 years, he’s calm and comfortable inside a classroom. As the bell rang ending the interview he smiled at me.

“Well you helped pass the time,” he said.

Mr. Hyland will tell you a few stories if you ask, weaving together things from another time and the school around him. Hyland watched the schools around him change and floated like a boat on a troubled sea. There didn’t seem to be much difference to him between kids in the 60s and kids now, between Staten Island and Denver, he’s an old fashion craftsman, and his craft is teaching.